Tanzania’s push to curb loan sharks sparks debate over policy signals

When government officials call for lower lending rates, markets may perceive this as political pressure, potentially weakening monetary policy credibility

Dar es Salaam. Tanzania’s drive to rein in high-interest lending has reignited debate over whether government messaging risks blurring the line between regulatory oversight and monetary policy.

High-cost loans, particularly from predatory lenders or individualised “loan sharks” (mikopo umiza), continue to strain households, especially among women and young people, prompting authorities to take decisive action.

In Parliament in Dodoma on June 27, the Deputy Minister for Finance, Mr Laurent Deogratius Luswetula, said the government is “prepared to ensure that all lending institutions comply with regulations and that a draft framework for managing digital loans will be implemented in the 2026/27 financial year.”

The measures include suspending unlicensed lenders, closing hundreds of digital loan programmes, and issuing guidance to promote transparency, ethical conduct, and consumer protection.

These actions align with global practices, as countries such as Kenya and India have similarly strengthened oversight of informal and digital lenders.

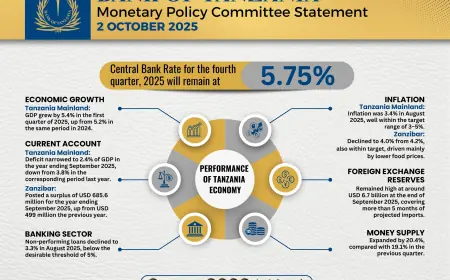

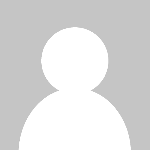

However, these interventions exist alongside the Bank of Tanzania’s (BoT) management of the Central Bank Rate (CBR), creating potential tension.

The Bank Rate is intended to influence liquidity and overall borrowing costs, primarily as a tool for controlling inflation.

When government officials call for lower lending rates, markets may perceive this as political pressure, potentially weakening monetary policy credibility.

Global precedents suggest that direct intervention in interest rate pricing can yield counterintuitive results.

In markets where interest rate caps or heavy-handed administrative controls were introduced, the unintended consequence was often a credit crunch.

Lenders frequently withdraw from high-risk segments, such as small and medium enterprises (SMEs) or informal traders, because capped returns do not justify the associated default risks.

Economists warn that such measures can drive borrowers back into the hands of even more dangerous, unregulated “loan sharks,” undermining the very purpose of regulation.

In Tanzania, the government appears to frame these interventions not as market distortions, but as necessary corrections of a “market failure” regarding consumer protection.

The suspension of 69 digital lending applications and closure of 126 others demonstrates that the Ministry of Finance views the issue primarily through the lens of legality and ethics rather than liquidity management.

By enforcing the Microfinance Act of 2018 and the Banking and Financial Institutions Act of 2006, authorities emphasise that excessive interest rates are often symptomatic of unlicensed and unethical operations rather than legitimate competition.

International experience underscores the importance of clear boundaries between regulation and monetary policy.

In the United Kingdom, high-cost credit is regulated through conduct rules, while the Bank of England independently sets the base rate.

Similarly, in the eurozone, national authorities oversee lending practices, but the European Central Bank alone determines policy rates.

These separations preserve credibility and prevent market confusion.

In Tanzania, lending rates reflect not only the policy rate but also operational costs, risk premiums, limited competition, and the appeal of government securities.

The government’s current focus, however, is on licensing compliance, enforcement against unlicensed digital lenders, and expanding financial literacy, which has reached more than 64,000 citizens across 16 regions.

The attention on the upcoming 2026/27 digital lending regulations, together with ongoing literacy campaigns, signals a clear desire to formalise this sector.

For the BoT, the challenge remains to synchronise its broader Bank Rate objectives with these targeted regulatory crackdowns.

To avoid sending conflicting messages to international investors, government efforts to protect citizens from exploitative lending must be perceived as a permanent consumer-safety framework rather than temporary interference in the central bank’s independent mandate.

Ultimately, communication is central. Framing interventions clearly as regulatory and consumer-protection measures, while allowing the BoT full autonomy over the Bank Rate, would preserve coherence.

Without such clarity, mixed signals could undermine market confidence, particularly at a time when strong monetary discipline is critical for macroeconomic stability.

What's Your Reaction?

Like

0

Like

0

Dislike

0

Dislike

0

Love

0

Love

0

Funny

0

Funny

0

Angry

0

Angry

0

Sad

0

Sad

0

Wow

0

Wow

0